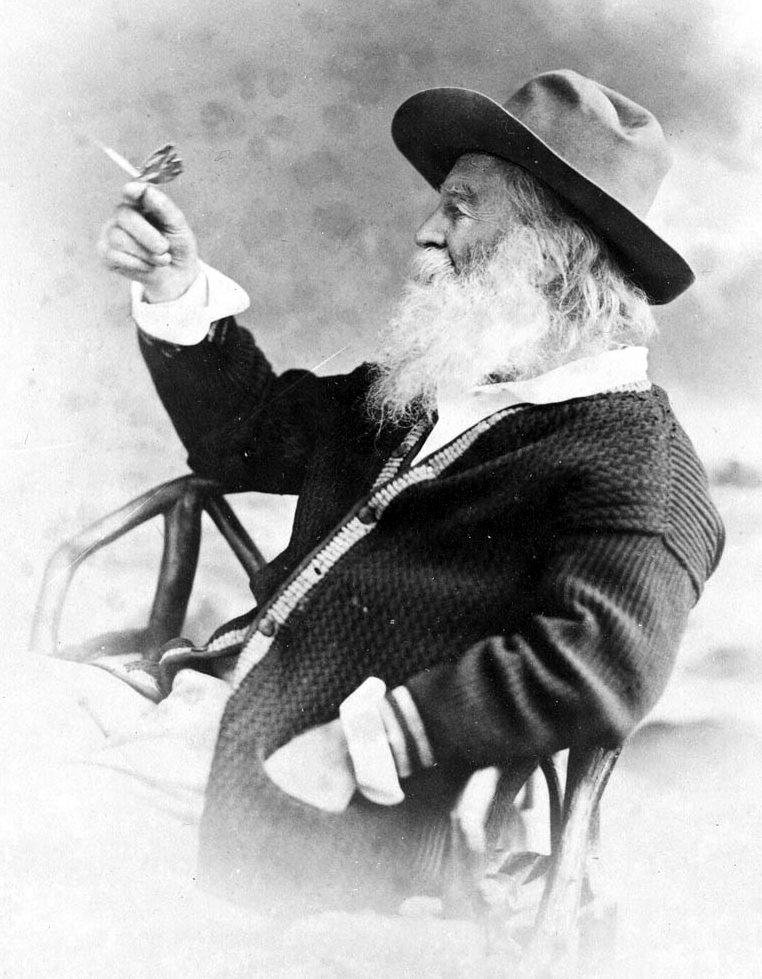

Walt

Whitman (1819–1892) is perhaps the most distinctly American of the

early U.S. poets. Alive and sprawling, Whitman’s poems are unorthodox and

fiercely democratic. His vision of freedom is well-articulated in the 1855

introduction of Leaves of Grass, where he writes: “This is what you

shall do: love the earth and sun and the animals, despise riches, give alms to

every one that asks, stand up for the stupid and crazy, devote your income and

labor to others, hate tyrants, argue not concerning God, have patience and

indulgence towards the people, take off your hat to nothing known or unknown or

to any man or number of men, go freely with powerful uneducated persons and

with the young and with the mothers of families, read these leaves in the open

air every season of every year of your life, reexamine all you have been told

at school or church or in any book, dismiss whatever insults your own soul, and

your very flesh shall be a great poem and have the richest fluency not only in

its words but in the silent lines of its lips and face and between the lashes

of your eyes and in every motion and joint of your body.” Whitman’s work

continues to be a major influence in the U.S. and abroad, exemplifying the

inextricability of content and form. As Whitman wrote in his poem “So Long!” …

“Camerado, this is no book, / Who touches this touches a man, / (Is it night?

are we here together alone?) / It is I you hold and who holds you, / I spring

from the pages into your arms—decease calls me forth.”